In 2012, together with m’colleague Brogan Bunt, I had the pleasure of creating and teaching a new subject at UOW called “Social Intersections“:

This subject examines how creative practice can engage with social forms and processes.

The aim is to encourage conceptually informed, interdisciplinary practice that reflects upon dimensions of social space and history. Students gain a critical understanding of relevant traditions of creative practice and develop individual and collaborative projects that reconsider the relationship between art and society.

The students did some really interesting projects and we had a bunch of excellent discussions in class about this “new” form of art, which engages with social relations as a material. We had good experiences with getting the students to use blogging to track their own progress throughout the semester.

I’m in the process of archiving the class blog, and clearing the decks so that in 2013, our new batch of students can start filling it up with their work.

I figured that some of the lecture notes from the subject might be more widely useful, so I’m cross-posting them on this here blog. Below I have cut and pasted an entry I wrote under the notional title of “Modes of Engagement”, which was intended to provide a cross-section (albeit incomplete) of ways in which artists might engage with the world, by acting “as” practitioners of other (non-art) disciplines…

– – –

My lecture will focus on a number of modes which might each be introduced by the words:

“THE ARTIST AS …”

For each mode, I’ll give an example or two, and discuss briefly how it has played out in particular situations. The intention here is to give you a broad range of approaches that you might consider adopting, adapting, critiquing, mixing, matching and mashing in your own practice.

(Standard disclaimer: the list is not exhaustive; the category-modes are mutable, arbitrary, overlapping etc; the examples given are convenient and not intended to be canonical; the analysis is necessarily shallow; and so on. In other words, caveat emptor!)

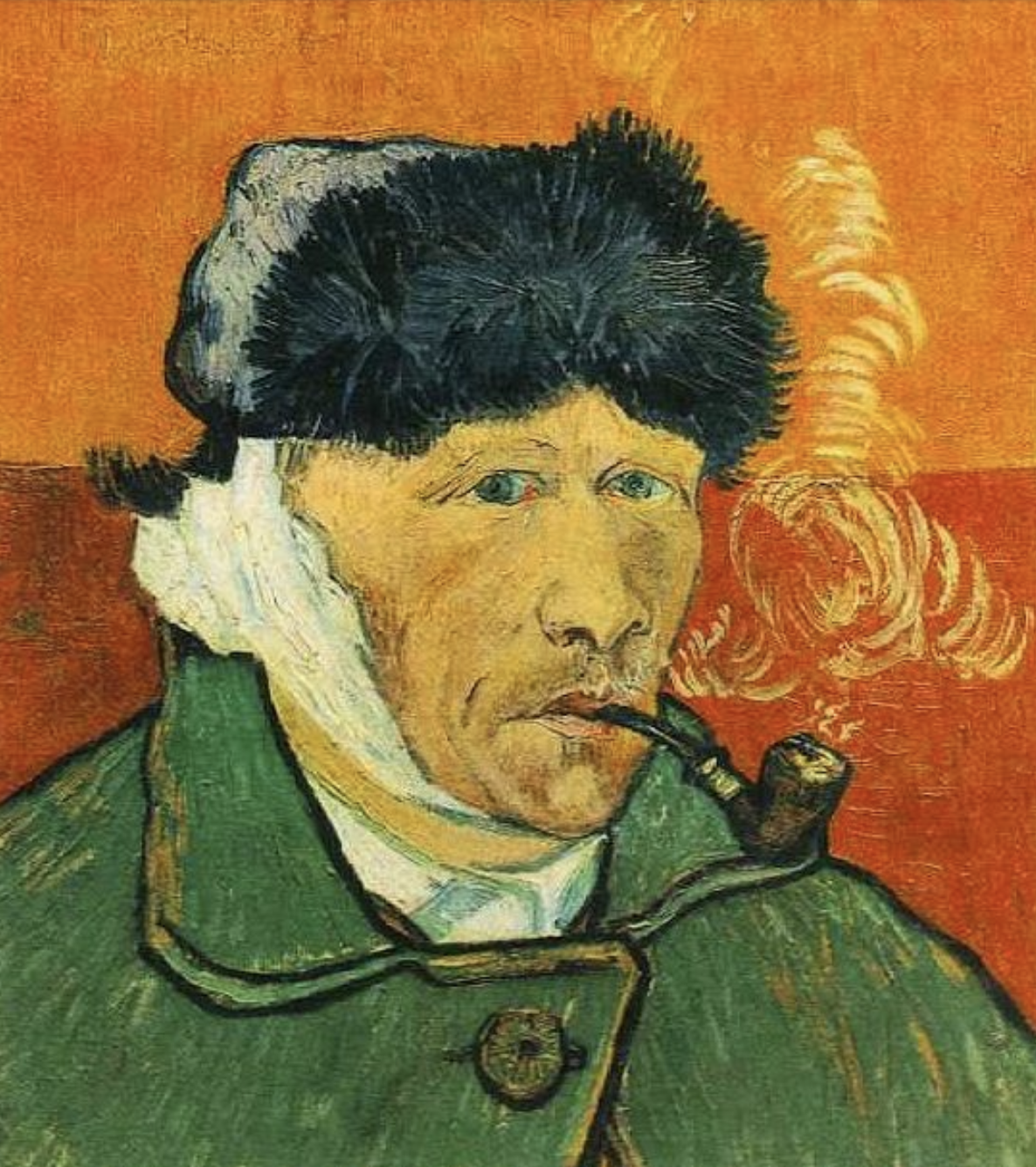

1. The Artist as Special Loner or Social Outsider

In this mode, “The artist” sees him/herself as a special category separate from mainstream society, and superior to it. The artist toils in private, or within a small community of similar outsiders. He is “poorly socialised” in terms of functioning as a normal citizen. (Perhaps it could be called a mode of “disengagement”, or in extreme cases, even misanthropy).

This mode is partly mythologised through popular imagery of the artist starving in a garrett.

Variants:

- The artist as an outsider to the artworld itself: ie, “outsider artists“, who are, typically, untrained and unaware of the required methods of maneuvering within the artworld;

- The un-artist (Kaprow) – but this is really a counter-variant, as Kaprow argued for “un-arting” one’s practice in order to regain continuity with everyday life, rather than separation from society;

2. The Artist as Social Critic

In this mode, the artist is unsatisfied with being a content provider within a given system (the art world, his/her local community, society in general, etc), and would prefer to critique the system itself. The artwork produced by this mode of artist attempts to change the status quo. In this mode, the artist sees him/herself as part of society, but simultaneously set apart from other citizens by this capacity for critique.

In one variant, The Artist as Aesthetic Philosopher is not content to leave the task of aesthetic analysis to critics. S/he critiques the systems of communication and distribution within the artworld, by making art. This can be seen in many works of Conceptual Art from the 1960s and 1970s. Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs, 1965, for instance is a classic of the genre:

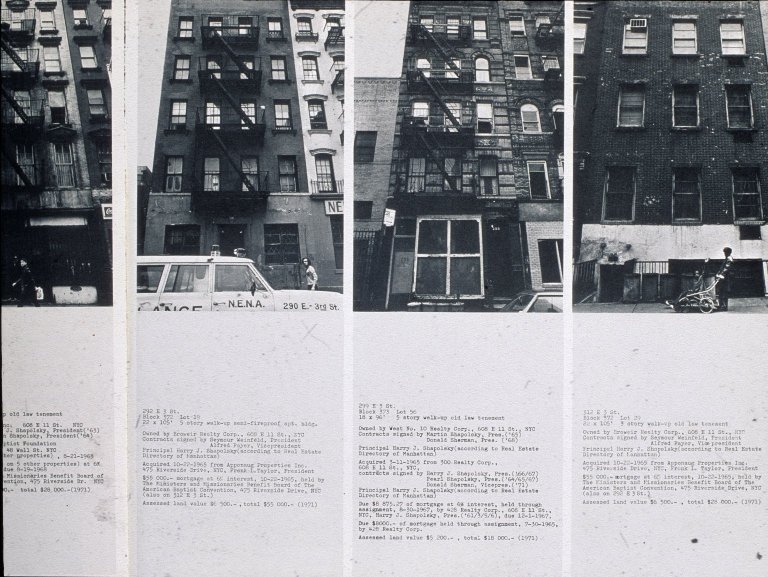

A much cited example of art as social critique is Hans Haacke’s “Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971”, which uses art to trace the intersections between the art world and the world of power and property in New York. This is an early example of what has been called “institutional critique“:

Variant:

- The Artist as Activist;

3. The Artist as Citizen

In opposition to the notion of Artist as Special Loner, the Artist as Citizen sees his/her work as continuous with the work of fellow citizens. Artists, in this instance, do not feel that they deserve special treatment, and do not aspire to be discovered at some unspecified time in the future when society (perhaps) “catches up” to their advanced ideas. Rather, the artist working in this mode desires to be a contributing member of society in the here and now.

In The Artist as Citizen, Linda Frye Burnham writes:

We have often said that art is essential to the life of the community, and if we’re right, then every community ought to have its own artist; a professional who is called on when the town plan is being laid or revised, who consults on celebrations and events of all kinds, as essential to the town as the plumber and the schoolteacher and the mayor.

Burnham gives the example of David Harding, who has practiced as a “town artist” for many years in the UK, participating as an employee of the town council in its planning division. Some of his works from the 1970s seem to be templates for participatory community art projects carried out around the world in the decades to follow:

[Children cementing their tiles to a wall. 1970]

[‘Path Poem’, David Harding with Alan Bold. 1976]

Another example is Brian Miller, Town Artist of Cumbernauld:

[Miller was] employed in the department of town architecture and planning, effectively a civil servant with all the standard terms of contract and retirement at the age of sixty-five. His position within this department meant that he became involved in the early discussions about how to shape the new town.

More recently, the notion of the artist as citizen has been taken up more loosely, in broad social movements where the artist is not an employee of the state, but rather participates in social change actions.

Variants:

- An interesting Aussie variant of the Artist as Citizen is The Artist as Family, a group working in rural Victoria, creating projects as a family unit. Here’s an image from their project Food Forest (Sydney, 2010-onwards):

- The work of The Artist as Citizen often overlaps with the mode of The Artist as Activist (see below);

4. The Artist as Activist

In this mode, the artist aligns him/herself with social activists working in “the real world”. Not content to produce work consisting of social critique, within the bounds of the art world, this mode of artist ventures forth to join activists at large in social causes.

In Australia, an example of this is the Art and Working Life programme, begun in Australia in the late 1970s. Artists Ian Burn and Ian Milliss argued that artists should work within union movements – they should be seen as aesthetic workers within the movement – rather than art being a luxury activity which sits apart from class struggle.

The continuing threat of rising unemployment, the fight to maintain real wage levels and the quality of working conditions, the defence of the industrial rights of working people, the indiscriminate introduction of new technology and its impact on jobs and the economy, the erosion of welfare levels and services . . . these are issues absorbing the energies of trade unionists and the Art and Working Life programme can and should contribute to those struggles.

Artist Birgitte Hansen created numerous gorgeous banners for the Australian union movement (this one from 1983):

Clearly there is a risk that, in this way, art becomes “merely utilitarian or functional” – but doesn’t art always have a social function (even if it is not immediately evident)? This is a discussion worth having!

There are countless examples of artists working as activists, individually (rather than as part of a group), within their practice. Here are two:

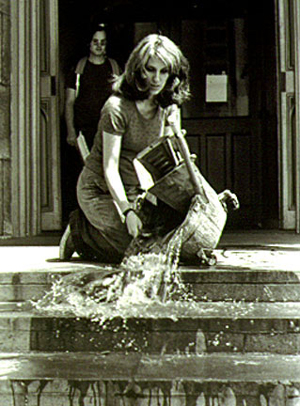

Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote a manifesto in 1969 entitled Maintenance Art – her aim was to draw attention to the crucial role of domestic activities (cooking, cleaning and child-rearing) in the functioning of society. Her performances during this period often involved scrubbing or cleaning museums:

[Mierle Laderman Ukeles, “Maintenance Art Performance Series”, 1973-74]

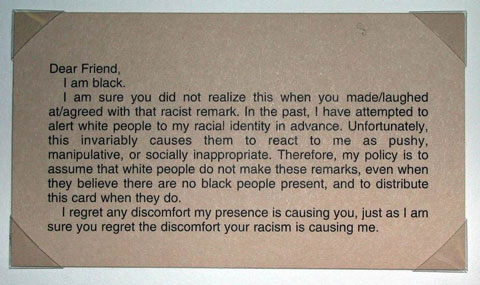

“Piper, a light-skinned African-American woman, had these cards printed to offer to individuals who made assumptions about her identity. One was given to individuals who, assuming she was white, did not hesitate to make racist remarks about Blacks in her presence. The other card was to be given to individuals who assumed that she was sexually available because she was unaccompanied.” (quote from here).

Variants:

- Protest Art;

- The Artist as Troublemaker;

- The Artist as Prankster;

- The Artist as Social Worker;

- The artist as Nature’s Social Worker;

- The Artist as Peacemaker;

- The Artist as Anti-Artist;

- The Artist as Anti-Anti-Artist;

- The Un-Artist;

- The Artist as Teacher / Shaman;

5. The Artist as Ethnographer

Ethnography is a discipline in the social sciences which (to paraphrase wikipedia) “studies people, ethnic groups and other ethnic formations, their ethnogenesis, composition, resettlement, social welfare characteristics, as well as their material and spiritual culture.”

So if you’re an artist wanting to explore social relations, ethnography and its methods (participant observation, field notes, interviews, surveys, etc) might seem be a good model to follow.

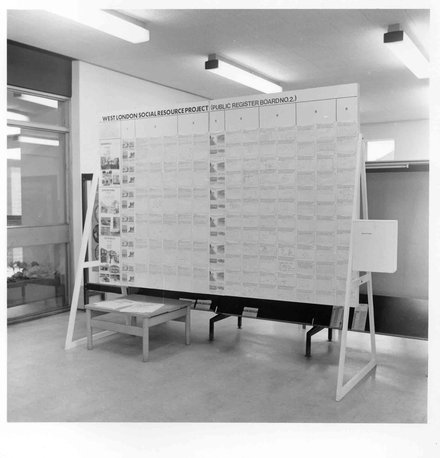

One artist who has been working within specific communities for many years is Stephen Willats. The following images are from his West London Social Resource Project, 1972:

Art theorist Hal Foster identified and critiqued this mode in his 1996 essay “The Artist as Ethnographer?“. For Foster, artists who work as pseudo ethnographers may have positive intentions vis-a-vis the communities they work within, but there are ethical risks involved in the process. He writes:

…the quasi-anthropological artist today may seek to work with sited communities with the best motives of political engagement and institutional transgression, only in part to have this work recoded by its sponsors as social outreach, economic development, public relations… or art.

[…and also…]

Consider this scenario, a caricature, I admit. An artist is contacted by a curator about a site-specific work. He or she is flown into town in order to engage the community targeted for collaboration by the institution. However, there is little time or money for much interaction with the community(which tends to be constructed as readymade for representation). Nevertheless, a project is designed, and an installation in the museum and/or a work in the community follows. Few of the principles of the ethnographic participant-observer are observed, let alone critiqued. And despite the best intentions of the artist, only limited engagement of the sited other is effected. Almost naturally the focus wanders from collaborative investigation to “ethnographic self-fashioning,” in which the artist is not decentered so much as the other is fashioned in artistic guise.

An important question for artists working in this mode to consider is, what unique properties/methods do they bring to the world of “social studies” as artists?

variants:

- The Artist as Documentary Maker;

- The Artist as Auto-Ethnographer;

- Artist as Archaeologist;

- The Artist as Historian / Archivist / Researcher;

- The Artist as Ecologist;

6. The Artist as Artist.

Huh? What could that possibly be?

[over and out, for now…]

-Lucas